Förderjahr 2024 / Stipendium Call #19 / ProjektID: 7335 / Projekt: Building Knowledge Graphs for Under Resourced Languages

As the digital world continues to grow, questions arise about how inclusive and multilingual it truly is. Many languages remain underrepresented online, limiting access and participation for millions of speakers.

Is the Digital Space Multilingual?

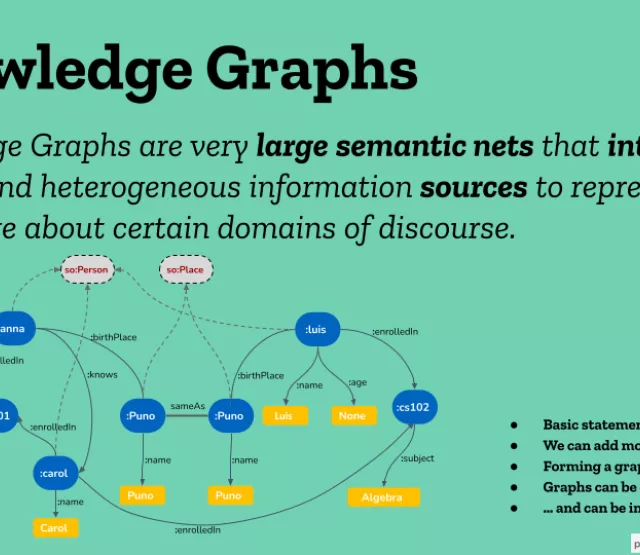

The digital space is dominated by few languages, such as English, Spanish, and few more, creating a significant barrier for speakers of under-resourced languages (URLs), whose languages are not represented there. This means that the limited availability of resources, including text corpora, large language models, and language technologies for URLs, limits their access to information and participation in the digital space. Knowledge Graphs (KGs), which are large semantic nets that integrate and represent knowledge from various domains, have proven to be very important for supporting the development of applications in high-resourced languages. For instance, major technology companies such as Amazon, Google, Microsoft and others have been collecting all the data and knowledge from the web with the aim of building KGs that can support their applications and services in English, Spanish, and a few other languages. However, the potential of KGs to support URLs is currently not deeply explored, pointing out significant challenges.

What are the Challenges?

- A core challenge lies in the data, mainly web data, used by tech companies to build their own KGs. Web data might lead to over-representation of certain viewpoints, languages, and topics, while neglecting others, particularly those belonging to Under-Represented Communities (URCs) and their languages. As a consequence, we might face services and (AI-)applications that perpetuate these biases, resulting in less correct and less complete representation of the knowledge of the world. Furthermore, current KG construction methods lack transparency and equity regarding the knowledge and language of URCs. Recent studies highlighted the presence of social and technical biases throughout the KGs lifecycle, e.g., biases can emerge during KG creation, hosting, curation, and deployment.

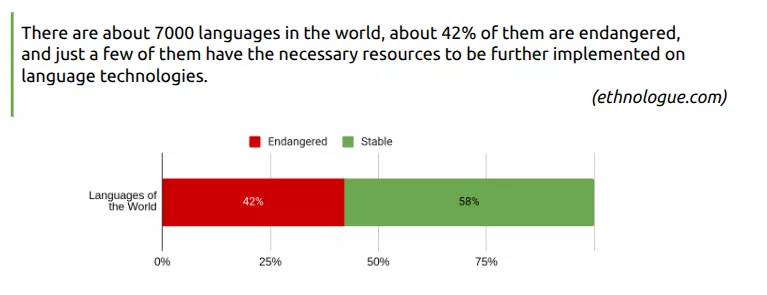

- There are about 7000 languages in the world, about 42% of them are endangered, and just a few of them have the necessary resources to be further implemented on language tech- nologies, e.g., only 9 languages are supported by Amazon Alexa and only 29 languages are supported by Google Assistant. Under-resourced languages are marginalized by society, minoritized by dominant languages, and excluded from decision-making processes.

Towards a Multilingual Approach

Despite the challenges mentioned above, KGs offer a well adopted technology and approach to support the representation of multilingual data, fostering interoperability, reusability, and inclusivity of applications and services built on top of them. However, addressing the building of community- centred and language-aligned KGs is critical to unlocking their full potential for URLs. This requires a shift towards inclusive design principles that should illustrate how data from URCs is collected [15], modelled, processed [16], and shared [17] in and off KGs.

For addressing more inclusive design principles in knowledge acquisition for KGs, it is critical to study the ways in which multilingual speakers use, interact, and generate language resources to communicate across contexts and tasks [18]. In order to understand the linguistic diversity in URCs, crosslinguistic awareness and language portraits can play an important role.

- Crosslinguistic awareness can be a good framework to understand – in terms of cognition, communication, identity – the relation and interaction between different languages in URL speakers’ mind [ 19], who are multilingual (i.e., speakers of an indigenous language and other dominant languages).

- Language portraits allow the representation of a speaker’s linguistic repertoire in a visual format, for instance in a body-silhouette or a tree, which nowadays can be implemented using online tools. To proceed with this method, speakers are asked to pick a colour for each language they know, and colour the body-silhouette language portrait, then create notes about the languages, colours, and placements choices. Afterwards, the insights from the language portraits can inform the design, collection, and modelling of KGs for URLs.

A KG for an under-resourced language could be designed to reflect the specific ways speakers of a language use it for thinking, learning, communicating, and expressing their identity. Furthermore, the outcome of the portraits can support the development of more detailed and culturally sensitive representation of linguistic knowledge in KGs, e.g., focusing on specific vocabularies that are relevant for communication in URCs.

Looking to the future

Future research needs to prioritize the biases in current KGs, promoting responsible building of applications and ensuring that the benefits of this technology are extended to all language communities.